Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

Cardiac surgery: what can you do in your practice?

Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

Read

Cardiac surgery is one of the least commonly performed types of surgery in veterinary medicine. Open cardiac surgery necessitates that circulation be arrested during the procedure by inflow occlusion or cardiopulmonary bypass. Ligature placement using hand ties are useful in such situations and the ability to place hand-tied knots (vs. instrument tieing) should be considered a fundamental skill for cardiac surgeons. Secure knot tieing is critically important to successful cardiac surgery.

Patent ductus arteriosus

PDA is the most common congenital heart defect of dogs; it also occurs in cats. PDA causes a left-toright shunt that results in volume overload of the left ventricle and produces left ventricular dilation and hypertrophy. Progressive left ventricular dilation distends the mitral valve annulus causing secondary regurgitation and additional ventricular overload. This severe volume overload leads to left-sided congestive heart failure and pulmonary edema, usually within the first year of life. Atrial fibrillation may occur as a late sequela due to marked left atrial dilation.

Surgical treatment

Surgical correction of PDA is accomplished by ligation of the ductus arteriosus. Ligation of PDA is considered curative and should be performed as soon as possible after diagnosis. Secondary mitral regurgitation usually regresses after surgery due to reduction in left ventricular dilation. Inadvertent ductal rupture during dissection is the most serious complication associated with PDA repair. The risk of this complication decreases as the surgeon’s experience increases. Small ruptures, especially those on the back side of the ductus, often respond to gentle tamponade, but will enlarge and worsen if dissection is continued. Large ruptures must be controlled immediately with vascular clamps and then repaired with pledget-buttressed mattress sutures. Once bleeding is controlled, a decision must be made whether to continue surgery, or to abandon surgery in favor of repair at a later time. Second surgeries are more difficult due to adhesions at the surgical site, so complete occlusion should be attempted during the initial procedure, if possible. Often, simple ductal ligation is not possible after a rupture has occurred. In such instances, surgical alternatives include ductal closure with pledget-buttressed mattress sutures or ductal division and closure between vascular clamps. The divided ductal ends are closed with a continuous mattress suture oversewn with a simple continuous pattern. Ductal closure without division is safer than surgical division, but re-cannulation of the ductus may occur. Because ductal division requires added technical expertise, it should be undertaken only by experienced surgeons.

Surgical technique

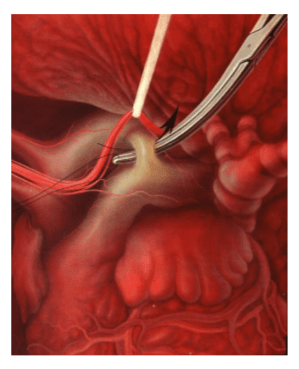

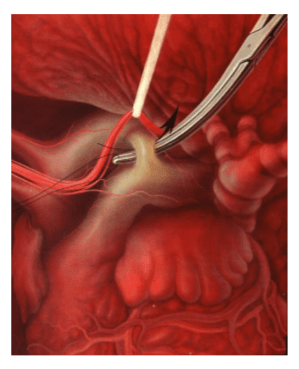

Perform a left 4th space intercostal thoracotomy. Identify the left vagus nerve as it courses over the ductus arteriosus and isolate it using sharp dissection at the level of the ductus. Place a suture around the nerve and gently retract it. Isolate the ductus arteriosus by bluntly dissecting around it without opening the pericardial sac. Pass a right-angle forceps behind the ductus, parallel to its transverse plane, to isolate the caudal aspect of the ductus. Then, dissect the cranial aspect of the ductus by angling the forceps caudally approximately 45 degrees. Complete dissection of the ductus by passing forceps from medial to the ductus in a caudal to cranial direction. Grasp the suture with right-angle forceps. Slowly pull the suture beneath the ductus. If the suture does not slide easily around the ductus, do not force it. Regrasp the suture and repeat the process, being careful not to include surrounding soft tissues in the forceps. Pass a second suture using the same maneuver. Alternatively, the suture may be passed as a double loop and the suture cut so that you have 2 strands. Slowly tighten the suture closest to the aorta first. Then, tighten the remaining suture.

[...]

Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

Comments (0)

Ask the author

0 comments