Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

Urethra

Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

Read

Surgical Management of Urethral Calculi in the Dog

Don R. Waldron

Introduction

Passage of urinary bladder calculi from the urinary bladder into the urethra may result in partial or complete urinary obstruction especially in the male dog. Calculi may lodge anywhere in the urethra but most commonly cause obstruction by lodging at the base of the os penis. The urethra at this level is narrow and does not distend owing to the presence of the os. Urethral calculi are less common in females as urethral distensability allows passage of the calculi in many cases. Dogs with partial or total urethral obstruction strain to urinate and pass little or no urine. Depending upon the duration of obstruction, the animal may be anxious, depressed or weak and the urinary bladder is usually distended. If the animal is azotemic and prolonged obstruction has occurred, vomiting and hypothermia may be present.

Preoperative Management

Complete urethral obstruction causes postrenal uremia that results in electrolyte and acid-base imbalance. Hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis are the most likely abnormailities. The goals of therapy are correction of any fluid or acid-base imbalance by intravenous fluid administration and relief of urethral obstruction. Normal saline (0.9%) is the fluid of choice although Ringer’s may also be used.

Urethral obstruction is relieved by catheterization or a combination of cystocentesis and catheterization. Tranquilization or sedation with narcotics or ketamine/diazepam, or propofol may be necessary during efforts to establish urethral patency. In some cases, general anesthesia is preferred especially if the animal is metabolically normal. A urinary catheter is advanced to the level of obstruction and sterile saline infused under pressure in an effort to hydropulse the stones retrograde into the urinary bladder. Liberal lubrication of the catheter and inclusion of sterile lubricant within the fluid may assist in dislodging the obstructing calculi. The veterinarian or assistant may assist in urethral dilation by performing a digital rectal exam and occluding the pelvic urethra simultaneously with fluid infusion. Sudden release of digital urethral occlusion may allow calculi hydropulsion. If initial efforts are unsuccessful, cystocentesis to relieve bladder and urethral pressure may permit successful hydropulsion. Some veterinarians report successful flushing of stones distally out the end of the penis by the method described and quick withdrawal of the catheter. It is imperative to maintain digital urethral occlusion proximally to flush stones distally. If attempts to move the calculi by catheterization techniques are unsuccessful, the veterinarian may attempt to bypass the obstructing calculi with a smaller catheter to relieve bladder distension.

Once successful passage of the catheter to the bladder has been achieved, the catheter is attached to a closed fluid/urine collection system.

Surgical Techniques

Prescrotal Urethrotomy

In most cases, urethral calculi are successfully hydropulsed to the urinary bladder allowing cystotomy and calculi removal as an elective procedure when the patient is able to undergo anesthesia and surgery safely. Urethrotomy is performed most often at the base of the os penis to remove obstructing calculi when hydropulsion fails to flush the calculi into the bladder. Alternatively, a scrotal urethrostomy may be performed as a permanent urinary diversion procedure, this procedure requires neutering the patient (see Scrotal urethrostomy).

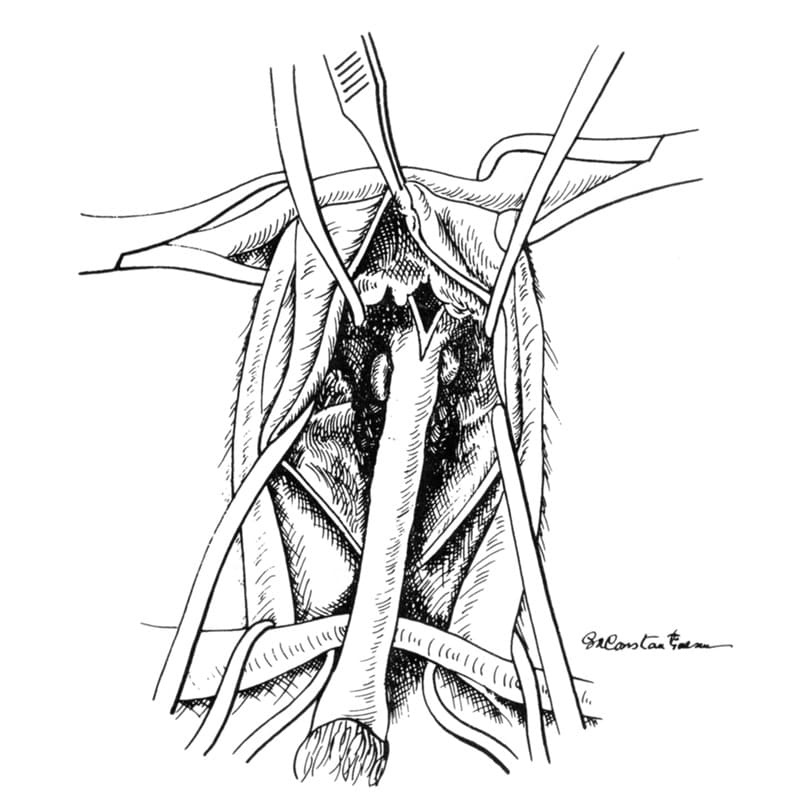

To perform prescrotal urethrotomy, a skin incision is made from the base of the os penis to just cranial to the base of the scrotum (Figure 31-1A). Subcutaneous tissue is sharply incised permitting identification of the retractor penis muscle which overlies the purplish colored corpus spongiosum. The retractor penis muscle is mobilized and retracted laterally. The surgeon grasps the urethra between the thumb and forefinger and elevates the urethra from the incision, this maneuver decreases hemorrhage as the corpus spongiosum and urethra are longitudinally incised directly over the obstructing calculi with a number 15 scalpel blade (Figure 31-1B). All obstructing calculi are removed by flushing or grasping calculi with a mosquito hemostat. Removal of all calculi, and patency of the urethra, is assured by successful passage of a urinary catheter to the urinary bladder proximally and distally through the penile urethra.

Surgical closure of the urethrotomy may be performed or the urethra and skin incisions allowed to heal by second intention (Figure 31-1C). If the urethra has been damaged by catheterization or calculi second intention healing is recommended. Suture closure of the urethra with 4/0 monocryl or polydioxanone on a tapered needle with simple interrupted sutures will reduce hemorrhage postoperatively but requires increased operative time. Gentle tissue handling and meticulous technique are recommended to decrease the chance of postoperative urethral stricture formation. Care is taken to appose the mucosal edges precisely. The subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed routinely. An indwelling urinary catheter is not routinely placed whether suture closure or second intention healing is selected. The incidence of urethral stricture following suture closure or second intention healing of the urethra has not been reported in clinical patients but appears to be low when urethral tissue is healthy and well vascularized.

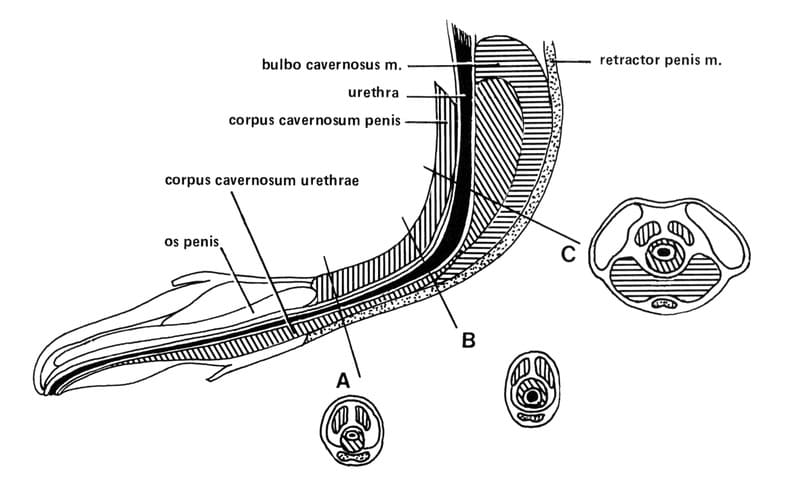

Figure 31-1. Prescrotal urethrotomy. A. Site of skin incision and dissection of subcutaneous tissue to the retractor penile muscle. B. Longitudinal incision into the corpus spongiosum and urethra after lateral retraction of the retractor penis muscle. C. Retention sutures in the corpus cavernosum and exposure of the urethral interior. After removal of uroliths, the urethrotomy can be left open or closed in a simple interrupted pattern (inset). (From Stone EA. Urologic surgery: an update. In: Breitschwerdt, EB, ed. Contemporary issues in small animal practice. Vol. 4. Nephrology and urology. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1986.)

Postoperative Management

Urine output, hydration status, renal function and electrolyte concentrations are closely monitored for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively. Post-obstructive diuresis may cause dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities including hypokalemia. If suture closure is not performed the dog will urinate from the urethral incision for 10 to 14 days as the wound heals. Bleeding from the urethra occurs concurrently with urination especially in the first few days following surgery if second intention healing is selected. Hemorrhage does not typically reach serious levels but does increase hospitalization time. Should stricture occur, scrotal urethrostomy is recommended.

Editor’s Note: Laser lithotripsy of urethral calculi can be an effective mode of therapy for relieving obstruction without surgery. Cystoscopic capability and laser access are required.

Scrotal Urethrostomy

Daniel D. Smeak

Introduction

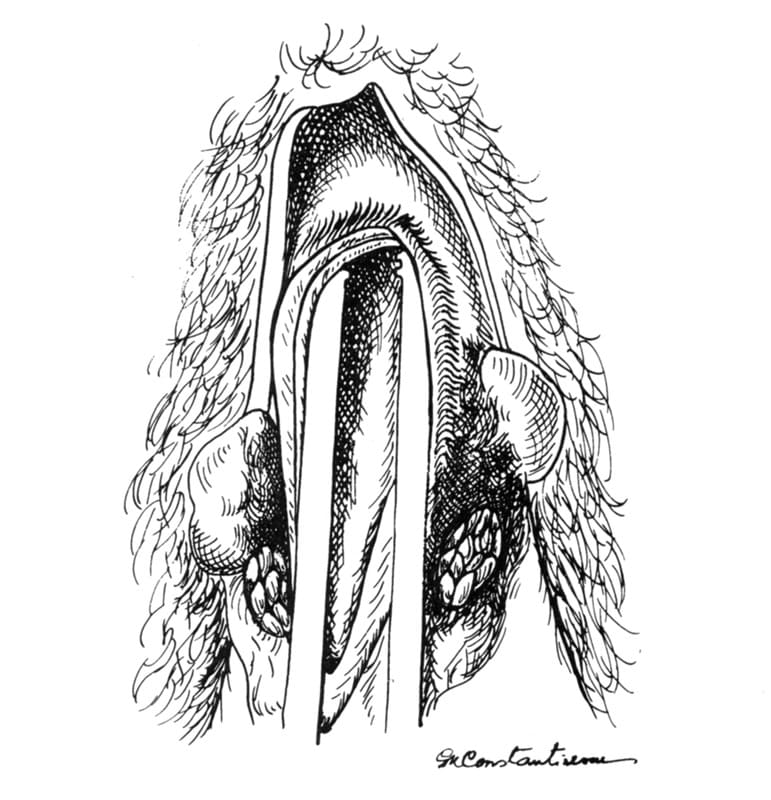

Scrotal urethrostomy is the procedure of choice in the canine when creation of a permanent urethral orifice distal to the pelvic urethra is necessary. Scrotal urethrostomy has several advantages over prescrotal, prepubic, or perineal urethrostomy. The membranous urethra in the region of the scrotum is larger and more distensible than the prescrotal urethra. These characteristics reduce the risk of stricture formation and calculi pass more readily through the stoma following urethrostomy. The urethra in the scrotal area is also more superficial and surrounded by less cavernous tissue than in the perineal region (Figure 31-2). Surgical exposure is easier, there is less tension on the urethrostomy, and the risk of hemorrhage or urine extravasation into periurethral tissues is reduced. Scrotal urethrostomy diverts urine directly downward and away from perineal skin. Skin surrounding the urethrostomy is kept dry and this reduces the risk of intractable dermatitis from urine scalding.1 Most urethral calculi are readily removed from the distal urethra or flushed back to the bladder by scrotal urethrostomy. I do not recommend a urethrostomy in the prescrotal region since urine expelled from the stoma often becomes misdirected and tends to soil the skin of the scrotum, inguinal region, and medial thighs and this area tends to stricture more readily than urethrostomies performed in the scrotal region.1,2 If castration is objectionable to the owner or the lesion is more proximal, however, other urethrostomy locations should be considered.3,4

Indications

Scrotal urethrostomy is indicated for the following conditions: (a) recurrent urethral calculi that are not responsive to appropriate medical therapy; (b) acute calculi obstruction in dogs anticipated having recurrent episodes (e.g., metabolic stone formers); (c) severe distal urethral wounds secondary to penile or os penis trauma; (d) urethral stricture distal to the scrotum from trauma or previous urethral surgery; and (e) diseases requiring amputation of the penis or prepuce and formation of a more proximal urethral stoma (e.g., extensive neoplasia in the region, penile strangulation, certain congenital diseases such as severe hypospadias, and deficiency in penile or preputial length).1 Because a permanent stoma that bypasses the normal opening of the urethra may increase the risk of ascending urocystitis, a urethrostomy should not be performed unless due consideration is given to the indications and complications of the procedure.5,6

If both urethral and bladder calculi are found in dogs requiring scrotal urethrostomy, I prefer to perform the urethrostomy first. After the urethrostomy stoma is created, the surgeon can flush any remaining (more proximally located) calculi back into the bladder, and then perform a cystotomy. This allows both normograde and antegrade urethral irrigation during cystotomy to ensure that all urethral calculi have been removed. If the cystotomy is completed first, any urinary stones remaining in the proximal urethra often cannot be removed via the scrotal urethrostomy, and are then flushed back into the bladder during retrograde irrigation.

A modified urethrostomy technique is described here because the standard simple interrupted scrotal urethrostomy technique often results in unacceptable bleeding and bruising complications.6 In a retrospective study of dogs undergoing standard scrotal urethrostomy, active hemorrhage (requiring patient hospitalization) was noted an average of 4.2 days following surgery; in some patients bleeding persisted up to 10 days.6

Figure 31-2. Schematic diagram showing cross sections of the penis and urethra in the prepubic A. scrotal B., and perineal C. locations. The urethra in the prescrotal and scrotal area is more superficial and is surrounded by less cavernous tissue than the perineal area. The scrotal urethra is more distensible and larger in diameter than the prepubic urethra, allowing easier passage of calculi and reducing the risk of postoperative stricture formation.

The following modified scrotal urethrostomy technique uses a continuous suture pattern and a three-needle bite sequence for urethrostomy closure.5 In my experience, this modification has dramatically reduced active bleeding, bleeding after urination, and bruising postoperatively. Furthermore, no stricture or suture line breakdown has been observed to date. This closure is also faster to perform.

The rationale for the modified technique is several fold. Simple continuous suture patterns produce a better seal by apposing tissues more completely. Continuous suture patterns require fewer knots, and irritation from “prickly” knot ears is reduced. Needle bites are placed closer together and this also improves urethra-to-skin apposition. Incorporation of a bite of tunica albuginea adds additional strength to the incision line and helps seal incised cavernous edges (see surgical technique). When the needle is passed outward from the urethra to skin, better apposition of cut surfaces results. All these advantages, I believe, help reduce suture line breakdown and hemorrhage.

Surgical Technique

The surgeon must obtain the owner’s consent for the animal’s castration before performing scrotal urethrostomy in intact dogs. Metabolic disturbances are stabilized in the obstructed patient preoperatively. I prefer to give an epidural administration of a narcotic to help alleviate pain in the immediate perioperative period. While the patient is under general anesthesia, the surgeon places the patient in dorsal recumbency with the rear limbs gently abducted and secured caudally. The proposed surgery site including the scrotum is clipped and scrubbed routinely and is draped for aseptic surgery. An elliptic full-thickness skin incision is made around the base of the scrotum. Hemostasis is maintained and the isolated scrotal skin is discarded (Figure 31-3). Enough skin should be left on the lateral aspect of the incision so no tension is placed on the urethrostomy during closure or with rear limb abduction. If there is any doubt, ample scrotal skin should be preserved and any redundant skin can be removed later in the procedure. If the dog is sexually intact, the testicles and spermatic cords are isolated and the dog is neutered in a routine manner (Figure 31-4). The underlying connective tissue is dissected to expose the paired retractor penis muscles, which appear as a thin brownish-tan band on the ventral surface of the penile shaft. The surgeon sharply dissects and mobilizes the retractor penis muscles, and retracts them laterally to expose the bluish corpus spongiosum urethrae (Figure 31-5). An appropriately sized red rubber urinary catheter is inserted retrograde from the normal penile opening, if possible, to outline and distend the urethra. The ventral midline of the urethra is sharply incised over the catheter with a #15 Bard-Parker scalpel blade. If a catheter cannot be inserted, the incision must be made carefully to avoid accidental laceration of the dorsal urethral surface. Blunt tenotomy or iris scissors are used to enlarge the urethral incision to 2.5 to 4 cm in length (approximately five to eight times the diameter of the urethra) to ensure sufficient urethral lumen size after healing is complete. The incision length appears excessive at first but after complete healing of the urethrostomy, the opening is approximately 2/3 to 1/2 the original length. The surgeon should stay directly on midline with scissors to reduce intra-operative and postoperative hemorrhage from cavernous periurethral tissue. Intra-operative hemorrhage is controlled with direct digital pressure. Electrocoagulation should not be used in tissues in the immediate vicinity of the urethrostomy site. The caudal limit of the incision is chosen to ensure that the new urethral stoma will allow urine to be diverted directly ventral from the ischial arch (Figure 31-6). A monofilament, nonabsorbable suture material (size 4-0 or 5-0) is selected for the urethrostomy because this material incites little inflammatory response and has minimal tissue drag. A taper-cut swaged-on needle is preferred to reduce the size of the needle tract through the cavernous tissue.

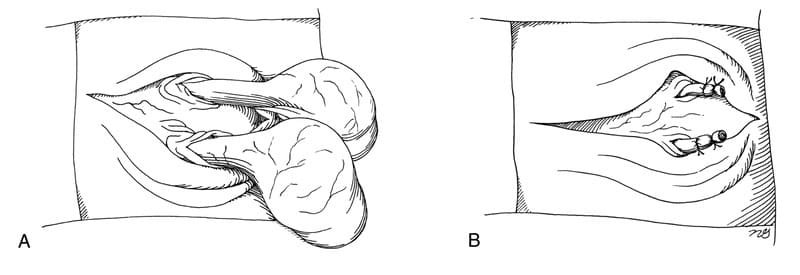

Figure 31-3. A. and B. An elliptical incision is made at the base of the scrotum. Enough lateral skin is retained to allow tension-free closure of the urethrostomy. Redundant skin can be resected later in the procedure.

Figure 31-4. A and B. The isolated scrotal skin is removed, and castration is performed.

Figure 31-5. A urinary catheter is placed retrograde from the penile orifice to help to identify the urethra. The retractor penis muscles are retracted laterally and the ventral midline of the urethra is visalized.

Figure 31-6. The ventral midline of the urethra is incised for 2.5 to 4 cm while immobilizing the penile shaft between the thumb and forefinger. The incision extends far enough caudally to ensure that direct ventral urine drainage can occur from the level of the ischial arch.

In addition, this needle can be inserted through the skin without difficulty and is less likely to cut friable urethral mucosa.

Sutures should appose the skin and urethral mucosa accurately, to avoid possible stricture formation. When excess tension is present, the surgeon should try to adduct the patient’s rear limbs before attempting closure. A deep suture line should be placed from the subdermal layer to the tunica albuginea if additional tension relief is necessary before closure of the skin and urethra.

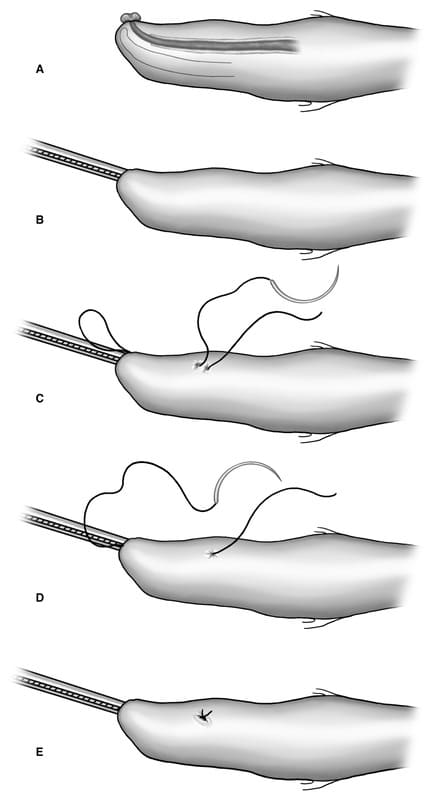

The needle is inserted in an outward direction from the urethral lumen to the skin for best apposition. The first suture is placed from the corner of the caudal urethral incision to the corner of the caudal skin incision. Each suture pass comprises three tissue bites. The sequence begins with a 2 mm bite of urethral mucosa. Next, the needle is passed through a 2 mm bite of fibrous tunica albuginea and, finally a 2 to 3 mm split-thickness bite of skin (Figure 31-7). A simple continuous suture line is used, with tissue bites 2 to 3 mm apart beginning caudally and working cranially (Figure 31-8). The urethral mucosa and skin margins are grasped gently and only when necessary to avoid excessive inflammation, which can lead to dehiscence and stricture. The urethral mucosa and skin are approximated without gapping. The suture line should not be tight and each suture pass should have even tension. After the first side of the urethrostomy is closed, a separate simple continuous suture closure completes the new stoma. The surgeon should excise any redundant skin in the cranial aspect of the incision to create a cosmetic closure. If the cranial aspect of the skin incision extends beyond the urethral incision, it is closed with simple interrupted sutures.

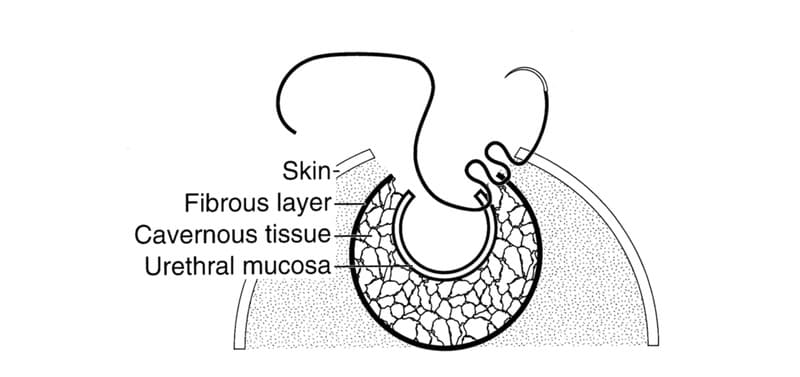

Figure 31-7. Three-needle bite sequence for closure of urethra to skin. The needle is inserted first through the urethral mucosa, followed by the tunica albuginea, and then a split-thickness bite of skin. The incised cavernous tissue is sealed between the urethral mucosa and tunica albuginea.

Figure 31-8. Suture the urethral mucosa to the skin beginning at the caudal aspect of the wound and continuing cranially. Place subsequent sutures in continuous fashion to complete one side of the urethrostomy. Another continuous line on the opposite side of the incision completes the procedure. Routinely close any remaining skin outside the urethrostomy.

Postoperative Considerations

Creation of a urethrostomy will not cure urinary tract infection or remove the source of urinary calculi. It can be expected that any procedure that shortens the functional length of the urethra such as urethrostomy, increases the risk of urinary tract infection.3 Strict aseptic procedures should be adopted during stoma inspection and urethral catheterization to reduce this risk. Since the urethrostomy is located distal to the pelvic urethra (the area that controls urethral flow) there is no concern about creating incontinence following surgery. Owners should understand that urethrostomy reduces but does not completely eliminate the risk of urethral obstruction by calculi. If obstruction occurs, these patients are usually readily managed by catheterization and hydropropulsion of the calculi.

An Elizabethan collar or side body brace is placed on all dogs immediately after urethrostomy until healing is complete; or about 2 to 3 days after suture removal. The incision area is kept clean but blood clots are not removed unless they obstruct urine flow. A film of petrolatum jelly is applied to the skin around the urethrostomy site once or twice daily until postoperative swelling is reduced (3 to 5 days) to reduce urine scalding of surrounding skin. Topical anesthetic agents (5% Xylocaine ointment, Astra Pharmaceutical Prod., Inc., Westborough, MA 01581) can be applied to the exposed urethra if the patient is showing discomfort during urination. Minor bleeding can be treated with application of direct pressure over the urethrostomy site and cold compresses. On rare occasions, if bleeding from the stoma is profuse and localized, additional sutures may be placed in gaps between the urethra and skin. Sedatives can also be used to reduce bleeding if the patient is hyper-excitable. Exercise is strictly limited because any episodes of excitement, could lead to excessive hemorrhage from the urethrostomy, and to reduce motion and tension at the stoma to reduce the risk of dehiscence. Dogs are usually hospitalized for the first two days since owners are often concerned about mild postoperative hemorrhage that is usually present especially during and just after urination. Urine samples collected via cystocentesis should be cultured routinely after antibiotics are discontinued to determine if urinary tract infection is present. Urinary calculi are submitted for quantitative analysis and the patient treated with appropriate antibiotic, dietary, and medical therapy once calculus type is known. Urine voiding habits should be monitored indefinitely to identify early signs of obstruction or infection. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used judiciously for 3 to 5 days after surgery to help reduce inflammation and pain.

Sutures are removed 10 to 12 days following the surgical procedure. Removal of a continuous suture line is more difficult than removal of simple interrupted sutures placed in the urethra. Migrating epithelium often partially covers exposed suture and sedation is necessary to remove sutures without causing pain and trauma.

Swollen, bruised, and painful areas of skin surrounding the urethrostomy may signal leakage of urine into the subcutaneous tissues. Placement of an indwelling soft urinary catheter is indicated in these dogs for three to five days, or until the edges of the urethrostomy are sealed. In general, catheters should be avoided because they increase the risk of urinary tract infection and may increase the risk of stricture. Dehiscence of the urethrostomy should be repaired primarily, without tension, using the materials and suturing techniques described previously if the tissues are healthy; otherwise allow the area is allowed to heal by second intention and either reconstruct the strictured stoma or divert urine through a more proximal urethrostomy site.

References

- Smeak DD, Newton JD: Canine scrotal urethrostomy, in Bojrab MJ, ed.: Current Techniques in Small Animal Surgery (ed 4) Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1998, pp 465-468.

- Bellah JR: Problems of the urethra: surgical approaches. Prob Vet Med 1:17-35, 1989.

- Dean PW, Hedlund CS, Lewis DD, et al: Canine urethrotomy and urethrostomy. Comp Contin Ed Pract Vet 12:1541-1554, 1990.

- Smeak DD: Urethrotomy and urethrostomy in the dog, Clin Tech in Small Anim Prac 15:25, 2000.

- Newton JD, Smeak DD: Simple continuous closure of canine scrotal urethrostomy: results in 20 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 32:531-534, 1996.

- Bilbrey S, Birchard SJ, Smeak DD: Scrotal urethrostomy: a retrospective review of 38 dogs (1973-1988). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 27:560-564, 1991.

Perineal Urethrostomy in the Cat

M. Joseph Bojrab and Gheorghe M. Constantinescu

Feline urologic syndrome (FUS), a synonym for lower urinary tract disease in the feline, can result from various single, multiple and interacting, or unrelated etiologic factors. Factors implicated in the development of FUS are infectious agents such as viruses and bacteria, diet, and urachal anomalies, especially bladder diverticula.

Crystalluria is a common clinical finding in cats and is characterized by microscopic precipitates in the urine. The most prevalent crystal type is struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate). In normal cats, these crystals are passed in the urine during normal micturition. Urine from cats with FUS contains crystals that coalesce with a matrix of mucus and debris, to form a macroscopic semisolid mass, or concretion. Crystal formation is enhanced in an alkaline pH and is inhibited in a more acidic pH.

Urethral obstruction has been associated with concretions and urethral plugs. Other causes of urethral obstruction are strictures, lesions of the prostate gland, and extraluminal masses that compress the urethral lumen. Obstruction of the urethra by plugs occurs commonly in male cats but infrequently in females.

The explanation for this difference resides in the anatomic differences in urethral structure between the sexes. The urethra in the male cat is long and narrow, whereas it is short and wide in the female.

Crystals composing a concretion have razor-sharp edges, which protrude from the concretion margins. In the male cat, at the root of the penis just proximal to the bulbourethral glands, the urethral lumen diameter narrows, creating a funnel effect. As a concretion passes down the urethra, it may become lodged at this point. Initially, the cat can usually force a concretion through the penile urethra by straining. This action, however, forces the sharp edges of the crystals into the urethral mucosa, resulting in multiple lacerations. This trauma results in hemorrhage, urethral inflammation, edema, and swelling, which decrease the urethral diameter even further. Passage of another concretion through the urethra results in an obstruction that cannot be dislodged by the animal. This situation requires emergency treatment to remove the urethral obstruction and reestablish urine flow.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of FUS is based on history, clinical signs, and palpation of a large, firm, tense bladder. The history may include urination in unusual locations along with increased frequency in attempts to urinate. This increased frequency may be mistaken for tenesmus by the client. Frequent licking at the genital area and occasional hematuria may also be present. With progression of the condition, the cat may become depressed, listless, or comatose. Prolonged obstruction results in hyperkalemia, which can lead to cardiac irregularities and subsequent death.

Medical Treatment

The first step in emergency treatment of urethral obstruction is to relieve obstruction. This can be done by catheterization of the urethra, which in the severely depressed or comatose patient can be accomplished without the use of anesthetics. If attempts to dislodge the obstruction are likely to result in additional urethral damage or to induce urinary tract infection, pharmacologic restraint should be considered. An ultrashort acting anesthetic should be selected for sedation since the cat may have metabolic abnormalities. Anesthetics must be given cautiously, because effective doses in patients with postrenal azotemia tend to be lower than in animals with normal renal function.

To relieve the obstruction, concretions lodged in the distal penis are first milked out by gently rolling the penis between the thumb and forefinger. Additionally, massaging the urethra through the animal’s rectum may help to dislodge abdominal or pelvic urethral concretions. Voiding is then induced by gentle urinary bladder palpation. If urethral massage and bladder expression fail to dislodge the obstruction, retrograde urethral flushing is attempted to dislodge the concretion into the bladder by hydropropulsion.

The penis is exposed, washed, and a 3.5-French open-ended tomcat catheter, lubricated with a sterile gel, is placed into the distal urethra. Once the catheter has been placed, the prepuce is grasped digitally and is retracted caudodorsally, so the urethra is parallel to the vertebral column. A 12-mL syringe containing sterile saline or lactated Ringer’s solution is then connected to the catheter by an assistant. Subsequently, fluid is forced through the catheter while the catheter is gently advanced; the catheter should remain parallel to the spine during this maneuver. This technique should force the concretion into the bladder. The catheter is then advanced into the bladder, which is then repeatedly flushed and emptied to remove as much debris as possible. This catheter is then removed and is replaced with a 5-French catheter cut to a length of 6 cm. This catheter is positioned so the tip is just past the root of the penis. This reduces the possibility of ascending cystitis. The catheter is sutured in place and is removed in 5 days. If urethral patency cannot be restored by this method, one should suspect a mural or periurethral lesion with or without an associated urethral plug.

Antibiotics are given for 30 days; three different drugs are used for 10 days each. The cat’s diet is changed to Prescription Diet Feline Multicare (Hills Packing Company, Topeka, KS). This diet is low in magnesium and tends to acidify the urine, thus decreasing crystal formation. The food should be salted to increase fluid intake and to promote diuresis, to flush out urinary bacteria and precipitates. Instead of salting the food, the owner may administer a 1-g salt tablet orally once a day. If obstruction recurs, perineal urethrostomy is indicated.

Perineal Urethrostomy

Preoperative Considerations

Cats who have had urinary tract obstruction are poor anesthetic risks. Diuresis after unblocking is indicated. Induction of anesthesia with an ultrashort-acting anesthetic agent followed by maintenance with a gas anesthetic is recommended.

Surgical Technique

The animal is prepared for aseptic surgery. The hair is clipped from the entire perineal area including the base of the tail. A pursestring suture is placed in the anus, and a 3.5-French open-ended tomcat catheter is placed. The animal is positioned on the surgery table in ventral recumbency with the hind legs draped over the end of a titled table. The tail is taped over the dorsal midline of the back, and the genital area is draped.

An elliptic incision starting halfway between the anus and scrotum is made around the scrotum and prepuce (Figure 31-9). If the animal is sexually intact, castration is performed. After the penis with accompanying prepuce and remaining scrotum are retracted dorsally, ventral dissection is begun with Metzenbaum scissors (Figure 31-10). All preliminary dissection is done ventrally until the bilateral ischiocavernosus muscles are located and cut with scissors at their urethral attachments (Figure 31-11). This technique frees the penis and allows the visualization of a ventral penile fibrous band from the pelvic diaphragm located on the midline between the penis and the ischial arch. This structure is then cut, further freeing the penis.

At this point, dorsal dissection is begun. All dorsal dissection is accomplished close to the urethra. Metzenbaum scissors are used to cut and bluntly dissect the attachments circumferentially, further freeing the urethra and allowing it to be retracted caudally. The dorsal white V-shaped uterus masculinus is now visible and is cut close to the urethra (Figure 31-12). Care must be exercised during the entire dissection not to damage the rectum (dorsally) and the nerves that innervate the rectum and bladder neck. Such damage is avoided by keeping all dissection close to the urethra.

Figure 31-9. After the perineal area is draped and a urinary catheter is placed, an elliptic incision is made around the scrotum and prepuce.

Figure 31-10. The penis and prepuce are retracted dorsally, and ventral dissection is begun.

Figure 31-11. The ischiocavernosus muscle is identified and is cut with scissors close to the penile attachment.

Figure 31-12. Urethral dissection is completed by transecting the V-shaped uterus masculinus close to the urethra.

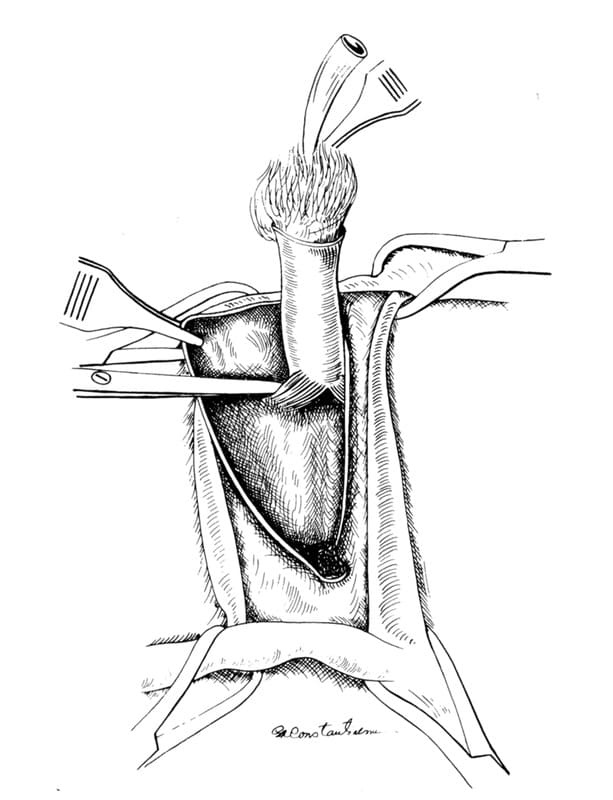

The dissected penis is grasped in the surgeon’s left hand, with the index finger under the penile crus. A No. 10 scalpel is used to incise over the catheter on the dorsal midline of the urethra (Figure 31-13). The incision is carried into the lumen. The incision is extended 1 cm cranial and 2 cm caudal to the crus of the penis. Extension of the pelvic urethral incision more than 1cm cranial to the crus leads to severe incisional invagination when the incision is sutured. A 1-cm incision in the pelvic urethra is adequate to provide the enlarged opening needed. The catheter is removed, and forceps are inserted into the pelvic urethra (Figure 31-14). The incision is now ready for suturing.

We recommend using 4-0 polydioxanone or polypropylene (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) with a swaged-on taper-cut needle for urethral suturing. The first suture is placed to approximate the most dorsal skin edges. The next suture, which begins the urethral suturing, picks up one skin edge and then passes through the dorsal roof of the urethra just cranial to the most cranial incision edge and then through the other skin edge (Figure 31-15A). When this suture is tied, the roof of the urethra is pulled up to the skin edge, thus lifting the urethra to the surface. Suturing is continued down the skin incision on each side, including the cut edge of the urethral mucosa in each stitch (Figure 31-15B). It is important also to include the edge of the corpus spongiosum (corpus cavernosum urethrae) within these urethral edge stitches to help control hemorrhage from the cut edge of the corpus spongiosum.

Figure 31-13. The urethra is incised into the lumen with a No. 10 scalpel.

Figure 31-14. After the incision is completed, the catheter is removed, and forceps are inserted into the pelvic urethra.

Figure 31-15. A. The first suture approximates the dorsal skin edges; then the first urethral suture is placed, engaging both skin edges and the pelvic urethral roof. B. Urethral suturing continues down the skin incision on each side.

After both sides of the skin incision have been sutured, the penis is cut off with scissors (Figure 31-16A) at the level of the caudal urethral incision. The cut end (Figure 31-16B) is sutured as shown in Figure 31-17. This helps to seal the cut end of the corpus cavernosum penis and eliminates much of the excessive postoperative hemorrhage often encountered with this surgical procedure. The final sutures are placed approximating the caudal skin edges (Figure 31-18). The wide end of the tomcat catheter is cut (approximately 2.5 cm), inserted into the new urethral opening, and sutured to the skin on each side (See Figure 31-18).

Figure 31-16. A. Excess penis is cut off with scissors at the level of the caudal incision. B. The cut end of the penis is shown, revealing the corpus cavernosum penis.

Figure 31-17. The exposed cut surface of the corpus cavernosum penis is sutured.

Figure 31-18. After suturing of the incision is completed, a 2.5-cm segment of catheter is sutured into the urethrostomy opening.

Postoperative Care

The pursestring suture in the anus is removed. An Elizabethan collar is placed on the cat to prevent licking of the incision. The same medical therapy as outlined previously is begun. The catheter is removed on the fifth postoperative day. The sutures and Elizabethan collar are removed on the tenth postoperative day.

The animal can be sent home during much of this postoperative period because urinary control is maintained even with the catheter, which is short and does not enter the bladder, in place. Owners must be instructed not to allow the cat to go outside while the sutures are still in place and to place shredded papers in the cat’s litter box, so litter will not stick to, contaminate, and irritate the incision.

Complications

The major complications of perineal urethrostomy are postoperative hemorrhage, subcutaneous urine leakage, infections, strictures, fecal and urinary incontinence, and rectal prolapse. Hemorrhage can be greatly reduced by taking care to include the cavernous tissue in the skin sutures. Infections can be decreased by eliminating postoperative contamination of the incision with litter and licking and by use of prophylactic antibiotics. Strictures can be prevented by adequate freeing of the urethra, to eliminate inpulling and suture line tension.

Urethroplasty for Stricture After Perineal Urethrostomy

Cats with urethrostomy stenosis present with stranguria producing only scanty urine and a palpably full bladder. If the stricture is due to improper dissection in the original surgical procedure (i.e., failure to transect ligaments and muscle attachments and free the urethra) or to failure to open the urethra properly, then the operation should be redone. If the original urethrostomy was done properly and a stricture subsequently occurred, a urethroplasty is performed.

The area around the stricture is clipped and prepared for surgery. The opening is located. The surgeon should use a 10X loupe to aid in visualization during surgery. A procedure similar to that for anal stricture (See Chapter 20) is used. Four cuts (dorsal, ventral, left lateral, and right lateral) are made with a No. 15 scalpel. Each cut incises the skin and underlying urethral mucosa. As each cut is made, the incisions open and form a diamond shape. The incisions are then sutured with 5-0 polydioxanone in the opposite direction in a manner similar to that shown in Figures 20-41 through 20-45. This technique alleviates the stricture.

Prepubic Urethrostomy in the Cat

Richard A. S. White

Surgical Anatomy

The unique anatomy of the cat’s urinary bladder neck and proximal urethra allows the feline urethra to be sectioned and urethrostomy performed at the prepubic level whilst preserving urinary continence. In male cats, the bladder is situated considerably more rostrally to the pelvic brim than in other domestic species; the trigonal region gives rise to an elongated bladder neck, often erroneously regarded as the preprostatic urethra, that reaches the pubic level before differentiating into the urethra proper. The urethral sphincter mechanism is located immediately distal to the trigone and hence section of the urinary conducting system at the junction of bladder neck and urethra, can be expected to preserve normal urinary continence. The combination of this relatively long bladder neck and the absence of a prostate gland encircling the urethra facilitates the creation of a urethral stoma at the posterior abdomen / prepubic level in the cat.

Indications

Indications for prepubic urethrostomy (PPU) include conditions that result in persisting urethral obstruction distal to the pelvic level. In contrast with the more common but increasingly controversial indications for perineal urethrostomy (PU), the indications for PPU are more easily recognized despite being less frequently indicated. Conditions in which distal urethral function is lost include salvage of perineal urethrostomy (PU) complications, management of cats with perineal skin deficits that preclude PU, complex urethral ruptures and strictures, granulomatous urethritis and neoplastic disease. Paradoxically, PPU requires considerably less surgical expertise and experience than PU and is easier to perform and this occasionally leads to its inappropriate substitution for PU.

The potential risks and complications of PPU are probably less frequently encountered than those associated with PU, however, the procedure should only be performed when all medical strategies have been exhausted and where PU is not considered to be a feasible option.

Preoperative Preparation

The more common indications for this procedure may be associated with some risk of urinary tract infection or bacteruria and hence perioperative antibiotic therapy based on urine culture from a sample obained by cystocentesis is usually appropriate. An opioid analgesic that can be continued into the postoperative period (e.g. buprenorphine) should be administered, and if renal function is normal, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapy may be appropriate to provide additional analgesia. The patient should be positioned in dorsal recumbency and the ventral abdomen including the pubic region should be aseptically prepared for surgery. Urethral catheterization is helpful but often not possible due to the obstructing indication; the absence of a urethral catheter should not unduly hinder the procedure.

Surgical Technique

A short caudal ventral midline incision is created immediately rostral to the pubic brim and a small pair of Gelpi retractors inserted to improve abdominal exposure. The bladder neck/ urethra is identified and gently freed from the surrounding periurethral adipose tissue as far distally as possible into the pelvic region (Figure 31-19). Care should be taken to avoid damage to the pelvic nerves located in the bladder neck area. The urethra is elevated using moistened umbilical tape or large hemostats (Figure 31-20) and then sectioned as far distally as possible; any bleeding from the distal urethra may be controlled by ligation or thermocautery. A catheter may be inserted into the proximal urethra at this stage to facilitate identification of the urethral lumen. The urethral stoma may be positioned in either a midline or a paramedian position. For the former option, the urethral opening is exteriorized through the laparotomy wound and the linea alba closed routinely proximal and distal to it, avoiding constriction of the urethra (Figure 31-21). Alternatively, the urethra can be drawn through a separate paramedian stab incision and the linea alba closed routinely. The subcutaneous dead space is closed with absorbable suture and the urethral stoma anchored to the skin with four simple interrupted (4/0 or 5/0) monofilament sutures (Figure 31-22). The urethral opening may be spatulated to increase the diameter of the opening and facilitate creation of the stoma if necessary.

Figure 31-19. Isolation of bladder neck/prepubic urethra via posterior laparotomy.

Figure 31-20. Elevation of bladder neck / prepubic urethra with umbilical tape.

Figure 31-21. Repair of linea alba allowing exteriorization of urethra.

Figure 31-22. Urethral stoma created by suturing to surrounding skin.

Postoperative Care

Patients normally benefit from receiving opioid analgesia for 48 hours and should be prevented from self-trauma by means of an Elizabethan collar. Litter trays with shredded paper instead of litter are provided to minimize the potential for debris adhering to the stoma site. Depending on the original indication for the procedure, it may be necessary to initiate management of underlying pre-existing lower urinary tract disease. Patients will need to modify their squatting posture for urination somewhat and the interval until this is successfully accomplished will vary between individuals. In the intervening period, any urine-staining or scalding of the skin in the inguinal region should be carefully managed to prevent secondary pyoderma complicating the healing of the urethral stoma. Urinary retention due to discomfort and pre-existing lower urinary tract disease should be managed with analgesia, striated muscle relaxants (e.g. diazepam) or smooth muscle relaxants (e.g. phenoxybenzamine); repeated catheterization of the urethra is avoided if possible.

Complications

Healing of the stoma is usually uncomplicated but, as with any urethrostomy procedure site, leakage of urine into the subcutaneous tissues surrounding the stoma before an effective seal has formed may lead to peristomal skin irritation and in severe cases, incisional dehiscence postoperatively. More chronic urine leakage can promote low-grade periurethral cellulitis which can lead to stenosis and stricture of the stoma; revision of stenosis may be complex. Stricture of the stoma occasionally occurs but the overall incidence is low. Occasionally, peristomal cellulitis can spontaneously occur in long-term PPU patients although the etiology for this is uncertain. Temporary urinary diversion by urethral catheterization or in some cases by tube cystostomy allows the cellulitis to resolve and patients will resume normal continent urination. Cutaneous urine scalding can be a transient problem in cats that do not modify their urination stance. Cranial transplantation of the prepuce with the stoma located inside or subpubic urethrostomy have been recommended to avoid this complication. These are more complex procedures and not usually necessary. Transient urinary incontinence may occur in some cats in the immediate postoperative period but usually resolves as the stoma heals. Some cats with pre-existing lower urinary tract disease may continue to be dysuric postoperatively which can be mistaken for incontinence; appropriate management of lower urinary tract disease should be initiated.

Conclusion

PPU is an acceptable surgical procedure for the management of cats where distal urethral function has been lost. The procedure is comparatively easy to perform and does not necessitate complex or prolonged postoperative care. Cats remain continent and most accommodate quickly to the change in posture necessary for urination without inguinal skin scalding. They will continue to lead a normal life. PPU should however be regarded as a salvage procedure and not substituted where medical management or PU would be a more appropriate operation.

Editor’s Note: Urinary incontinence may occur postoperatively in cats that have had PPU.

Suggested Readings

McCully RM: Antepubic urethrostomy for the relief of recurrent urethral obstruction in the male cat. JAm Vet Med Assoc 126: 173-179, 1955.

Ford DC: Antepubic urethrostomy in the male cat. JAm Anim Hosp Assoc 4: 145-149, 1968.

Mendham JH: A description and evaluation of antepubic urethrostomy in the male cat. J small Anim Pract 11: 709-721, 1970.

Snow HN: Surgical transpositions of the feline urethra necessary to ameliorate urolithiasis. J small Anim Pract 13: 193-200, 1972.

Emms SG: Antepubic urethrostomy in a cat. Aust Vet J64: 384-385, 1987.McLaren IG: Prepubic urethrostomy involving transposition of the prepuce in the cat. Vet Rec 122: 363, 1988.

Bradley RL: Prepubic urethrostomy: An acceptable urinary diversion technique. Prob Vet Med 1: 122-127, 1989.

Menrath V: Repair of a mid-pelvic urethral rupture in the cat using antepubic urethrostomy. Feline Pract 121: 8 ó 11, 1993.

Mahler S, Guillo JY: Antepubic urethrostomy in three cats and a dog: Surgical technique and long-term results. Rev de Med Vet 150: 357-362, 1999.

Baines SJ, Rennie S and White, RAS: Prepubic Urethrostomy: A long-term study in 16 cats. Vet Surg 30: 107-113, 2001.

Ellison GW, Lewis DD and Boren FC: Subpubic urethrostomy to salvage a failed perineal urethrostomy in a cat. Comp Cont Ed 11: 946-951, 1989.

Management of Urethral Trauma

Jamie R. Bellah

Introduction

Blunt abdominal trauma and traumatic displacement of bone fragments, especially pubic fragments, can lacerate the membranous urethra.1 Urethral injuries from other sources are less common but include gunshots, bite wounds, and iatrogenic trauma. The pelvic urethra may also be entrapped between pelvic fragments or mechanically compressed after elective pelvic surgery.2,3 Absence of skeletal injury does not preclude urethral damage. Traumatic urethral injury usually occurs in male dogs because the postprostatic pelvic urethra is fixed at the greater ischiatic notch. The incidence of urethral injury after car accidents is reported to vary from less than 5% to 11%.4

Diagnosis

Urethral injury is suspected when dysuria or anuria is observed. Hemorrhage from the urethral opening or hematuria, usually at the first portion of the urine stream, may be noted soon after injury. Urethral trauma is not excluded on the basis of an animal’s ability to void urine, however. Animals with urethral rupture may be depressed and anorexic, and penile urethral urine leakage may cause pyrexia and perineal or inguinal bruising and swelling. Uremia may or may not be present. A distended urinary bladder may be palpable. Proximal urethral lacerations or rupture may result in uroperitoneum, and clinical signs mimic those of a ruptured urinary bladder. Urine leakage may he detected from open wounds in the region of the pelvic cavity. If urine leakage is chronic a cutaneous urine fistula may result.4 Suspicion of urethral injury should be evaluated initially by positive-contrast urethrography using a water-soluble organic iodide preparation. Injection of air is avoided because it is difficult to delineate the site of urethral injury after air dissects periurethrally, and also because the use of air as the distending gas can result in fatal air embolism.5 Extravasation of contrast material occurs with both urethral laceration and urethral rupture, but in the latter instance, contrast material usually does not pass proximal to the complete tear. Cystoscopic examination may be used for evaluation of the lower urinary tract.6 Animals with proximal urethral trauma should also be evaluated by intravenous pyelography because concomitant ureteral injury may be present.

Surgical Techniques

Management of urethral injuries depends on the type of injury sustained and on the overall health of the animal. Uroperitoneum and its systemic metabolic effects must be resolved before lengthy surgical intervention. If uroperitoneum is present, its effects are resolved by urine diversion and intravenous fluid therapy to alleviate dehydration, acidemia, and hyperkalemia. Gentle catheterization of the urethra may be accomplished, depending on the site of the urethral laceration, but often the catheter tip finds the urethral defect and cannot be passed successfully. Urine can be diverted by percutaneous placement of a prepubic drainage catheter (Stamey catheter) or by insertion of a cystostomy tube (Foley or Pezzar catheter). Both techniques require sedation and (narcoleptic) local anesthesia unless the animal is moribund. Abdominal drainage may be necessary if more proximal urinary tract injury does not allow urine diversion by the aforementioned techniques.

Definitive surgical treatment of urethral injuries requires careful preparation because often the site of injury is difficult to access (postprostatic rupture). Lacerations may be managed solely by urethral stenting if a catheter can be successfully manipulated into the urinary bladder, and it may need to remain in place for 7 to 10 days. Conservative treatment of urethral injury requires that longitudinal mucosal continuity across the region of urethral trauma be present for successful urothelial repair. Despite the ability of urothelium to migrate, larger urethral defects require stenting for as long as three weeks for complete repair.7 Surgical correction of urethral rupture often requires pubic osteotomy to expose the severed urethra adequately. Sufficient exposure so debridement and precise anatomic anastomosis are feasible cannot be overly stressed.7 After debridement, simple interrupted sutures of absorbable material are used to perform the anastomosis over a urethral stent (catheter), with the knots outside the lumen of the urethra (Figure 31-23). The urethral mucosa must be anatomically apposed (without tension) or granulation tissue will be produced and contract the anastomosis, resulting in stricture despite the presence of a stent. Use of a catheter stent in addition to accurate suturing is believed to help prevent urethral stricture, however, overstretching the urethra may enhance fibrous tissue formation.8 Monofilament absorbable suture material such as polydioxanone (PDS), polyglyconate (Maxon), and poliglecaprone (Monocryl) are appropriate for urethral anastomosis. Interrupted appositional sutures are recommended and continuous patterns are avoided as the latter tends to “purse-string” the urethral lumen. Fine nonabsorbable monofilament sutures such as nylon and polypropylene may be used for urethral apposition, but because the sutures remain long after tissue healing is complete, they are not desirable.9 Urine diversion may be accomplished by placing a cystostomy tube (if necessary), and the urethral stent (catheter) remains to support the anastomosis and to divert urine away from the urethral wound to promote normal wound healing. The urethral stent should be large enough to maintain lumen size, but it should not be so large that it causes excessive pressure or tension on the anastomosis. If a large segment of pelvic urethra must be debrided, a permanent urine diversion procedure may be required. Antepubic urethrostomy or extrapelvic urethral anastomosis may be performed in those cases.

Figure 31-23. Anastomosis of the urethra requires accurate apposition of the urethral mucosa. Failure to do so results in stricture and dysuria.

Postoperative Care

Postoperative management of patients with urethral trauma and obstruction is intensive. Management of pain is often required for 12 to 24 hours. Animals must be restrained from prematurely removing urethral stents and cystostomy tubes. Restraint must be adequate, and may require Elizabethan collars, side braces, wire muzzles, and in some instances tranquilization. Prolonged catheterization (4 days or longer) often results in urinary tract infection, and periodic culture and susceptibility screening are important to avert a serious ascending infection. Proper use and care of closed urine drainage systems are mandatory. When urethral stents are removed, urine culture and susceptibility testing are done and antimicrobial therapy is based on those results.

Urethral stents (catheters) may be pulled when urothelium has bridged the urethral defect, as early as 5 days after repair. Careful injection of contrast material at low pressure is performed when contrast urethrograms are repeated, so the urethral wound is not disrupted. Difficult anastomoses, when repair is tenuous (or unsutured defects), may require urethral stenting for as long as 14 to 21 days.

The most common complication of urethral trauma repair is stricture. Stricture may occur early, resulting from dehiscence of the anastomosis, or a technically poor repair (tension or inadequate mucosal apposition), with a fibrous scar that may partially or completely occlude the urethral lumen. Stricture may also occur months after surgery or conservative management if contraction of periurethral scar tissue results in stenosis of the urethral lumen. Correction of urethral stricture may require resection and anastomosis or a urinary diversion procedure, however balloon dilatation of a urethral stricture in a dog has been reported. Strictures involving the more distal aspects of the urethra may be resolved by performing scrotal urethrostomy.

References

- Bellah JR. Problems of the urethra. Probl Vet Med 1989:1;17.

- Remedios AM, Fries CL: Implant complications in 20 triple pelvic osteotomies. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 6:202,1993.

- Messmer M, Rytz U, Spreng D. Urethral entrapment following pelvic fracture fixation in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2001;42(7):341-4.

- Bjorling DE. Urethral trauma. Slatter’s Textbook of Small Animal Surgery, 3rd Edition. WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia. 2003:1647-1651.

- Ackerman N, et al: Fatal air embolism associated with pneumourethrography and pneumocystograpy in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 176:1616, 1972.

- Messer JS, Chew DJ, McLoughlin MA. Cystocopy: Techniques and clinical applications. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2005;20:52-64.

- Boothe HW. Managing traumatic urethral injuries. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2000;15(1):35-39.

- Layton CE, Gerguson HR, Cook JE, Guffy MM. Intrapelvic urethral anastomosis – a comparison of three techniques. Vet Surg 1987;16:175-182.

- Jens B, Bjorling DE. Suture selection of lower urinary tract surgery in small animals. Comp Cont Educ Small/Exotics 2001;23:524-528.

Urethral Prolapse in Dogs

John A. Kirsch and J.G. Hauptman

Introduction

Urethral prolapse is an uncommon condition in the dog, and is most often seen in young male English Bulldogs.1,2 It has not been reported in female dogs. Urethral prolapse typically appears as a red to purple mass protruding from the orifice of the urethra. Clinical signs of urethral prolapse in the dog include excessive licking of the prepuce, preputial bleeding, and stranguria. Suspected causes of urethral prolapse in the dog include excessive sexual excitement, masturbation, and genitourinary infections or calculi.3,4 Its strong breed relation has also led to speculation that it occurs as a result of increased abdominal pressure secondary to chronic upper airway obstruction in brachycephalic breeds.1 This theory is consistent with the condition in humans, where it is proposed that there is poor attachment between muscle layers of the urethra associated with episodic increases in abdominal pressure.5 The strong breed association suggests a genetic predisposition. Differential diagnoses of urethral prolapse in the dog include trauma, urethritis, and neoplasia, particularly transmissible venereal tumor. Current described techniques for surgical treatment of urethral prolapse include manual reduction of prolapsed mucosa and placement of a temporary purse-string suture at the penile tip, which must be removed in five days,3,4 urethropexy,6 or resection of the prolapsed tissue and apposition of urethral and penile mucosa.1-4 Common post-operative complications associated with surgery are swelling and hemorrhage at the surgical site. The incidence of recurrence based on technique is unknown, although we have observed recurrence after all described techniques; subjectively, the catheter reduction and purse-string technique is the least likely to result in permanent correction. Treatment decisions for urethral prolapse should be made based on the following factors: 1) viability of prolapsed tissue, 2) history of recurrence in the patient, and, 3) which procedure, if any, has been performed prior to presentation for the current episode. Non-viable or severely traumatized urethral tissue is an indication for resection of prolapsed tissue.

Preoperative Care

Every effort should be made to rule-out underlying genitourinary disease. Radiographs, with or without contrast, may be performed to evaluate for calculi. Catheterization is helpful to assess patency of the urethral lumen. A rectal exam should be performed to evaluate the prostate and pelvic urethra. Urinalysis and urine culture are performed to rule-out underlying disease and infection. Castration should be discussed with the owner prior to surgery, since the procedure can be performed at the time of prolapse correction, and due to the purported connection of urethral prolapse to sexual excitement.

Surgical Techniques

Clipping the prepuce may not be recommended, as it may contribute to postoperative irritation. Prior to surgery, the prepuce is flushed with a dilute povidone iodine solution. Elective castration should be performed prior to correction of urethral prolapse, as it is the more sterile of the two procedures. The penis is manually extended from the prepuce and maintained in this position either by an assistant or by a Penrose drain tourniquet placed around its base (Figure 31-24). Extreme care should be taken with all techniques to employ gentle tissue handling and accurate suture placement, which will maximize success and minimize postoperative morbidity.

Figure 31-24. Extended penis with urethral prolapse.

Purse-string

A catheter or grooved director is used to reduce the urethral prolapse, and a purse-string suture is placed at the urethral orifice. The suture is tightened just enough the maintain mucosal reduction upon removal of the catheter. Care must be taken to ensure an adequate opening, as some localized swelling is expected following suture placement. If urethral patency is in question, one should elect a different corrective procedure.

Urethropexy

A lubricated grooved director is introduced into the urethral orifice, reducing the prolapsed urethral mucosa (Figure 31-25B). The director should be passed beyond the distal aspect of the os penis. If this fails to achieve reduction of all urethral mucosa, an assistant can grasp the penis at its tip and apply distal traction to invert the mucosa. Monofilament, 2-0 or 3-0, absorbable or nonabsorbable suture on the largest radius swaged-on tapered needle available is passed full thickness through the penis from the external surface, as far proximally as the needle curvature will allow, to the intraluminal surface directing the needle distally out the urethral orifice (Figure 31-25C). The grooved director is used as a receiving surface for the needle to prevent penetration of the opposite wall of the urethral lumen. The needle is then passed, in reverse fashion, from the urethral lumen to the external surface of the penis exiting just distal to the initial needle entry site (Figure 31-25D). The resulting full thickness suture is tied snugly with four throws, the initial throw being a surgeon’s throw (Figure 31-25E). This technique is repeated until three equally spaced sutures are placed. The grooved director can be removed/rotated between sutures. Following suture placement, an 8-10 French red rubber catheter is passed to confirm patency of the urethra. Sutures are not removed.

Figure 31-25. Urethropexy technique for treatment of urethral prolapse in the dog. A. Prolapsed mucosa visible at distal tip of penis, B. introduction of grooved director into urethral lumen to reduce prolapsed mucosa, C. first suture pass is external-to-internal, exiting urethral orifice, D. second suture pass from internal to external, exiting just distal to initial suture entry point, E. resulting full thickness suture is tied snugly. Process is repeated until reduction is maintained. All diagrams represent patient in dorsal recumbency.

Resection

A sterile catheter is placed in the urethra. An incision is made 90 to 180° at the base of the prolapsed tissue, resulting in a clean incision in healthy mucosa of urethra internally, and glans penis externally, using the catheter for support. The mucosal edges are apposed with 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable monofilament suture, preferably with a taper-point needle, in a simple interrupted pattern, spaced 1-2 mm apart. Absorbable braided suture (e.g.. Polyglactin 910) is also acceptable, but results in more tissue drag, and requires more throws for knot security, adding bulk to the repair. Care must be taken to achieve adequate bites of the urethral mucosa, and good mucosal apposition. This results in less second-intention healing and hemorrhage. Once apposed, the incision is completed around the orifice, and the process repeated. Proceeding as above, in stages, minimizes retraction of urethral mucosa, enabling better visualization and apposition.

Postoperative Care

The urinary catheter is removed following correction. Recovery should employ the use of sedatives and pain medication as judged necessary to ensure a quiet and smooth emergence from anesthesia. An Elizabethan collar should be worn at all times by the patient for a minimum of 10 days following the procedure, to prevent self-trauma. Exercise is limited to leash-controlled walks for 10 to 14 days. The prepuce should be monitored daily for irritation and swelling. It is normal for minor bleeding to be observed, intermittently and during urination, for 3 to 5 days post- operatively. Mild straining is also occasionally observed, but the urine stream should be consistent and adequate at all times following surgery. Underlying urinary tract disease or infection should be treated appropriately. Patients may be discharged with standard post-operative pain medication for elective soft-tissue procedures (NSAIDS). On an individual basis, short term (5 to 10 days) oral sedation with acepromazine is beneficial, and even advisable. Prognosis is good. We recommend the urethropexy technique as the easiest and most effective technique.6

References

- Hobson HP, Heller RH: Surgical correction of prolapse in the male urethra. Vet Med/ Small Anim Clin 1971;66:1177.

- Sinibaldi KR, Greene RW. Surgical correction of prolapse of the male urethra in three English Bulldogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1973;9:450.

- Fossum TW, Hedlund CS. Surgery of the urinary bladder and urethra. In: Fossum TW, ed. Small Animal Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book Inc., 1997:503-505.

- Boothe HW. Penis, prepuce, and scrotum. In: Slatter D, ed. Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1993:1336-1348.

- Lowe FC, Hill GS, Jeffs RD, Brendler CR. Urethral prolapse in children: Insights into etiology and management. J Urol 1986; 135:100.

- Kirsch JA, Hauptman JG, Walshaw R. A urethropexy technique for surgical treatment of urethral prolapse in the male dog.. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2002; 38 (4): 381-4.

Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

About

How to reference this publication (Harvard system)?

Author(s)

Copyright Statement

© All text and images in this publication are copyright protected and cannot be reproduced or copied in any way.Related Content

Readers also viewed these publications

Buy this book

Buy this book

This book and many other titles are available from Teton Newmedia, your premier source for Veterinary Medicine books. To better serve you, the Teton NewMedia titles are now also available through CRC Press. Teton NewMedia is committed to providing alternative, interactive content including print, CD-ROM, web-based applications and eBooks.

Teton NewMedia

PO Box 4833

Jackson, WY 83001

307.734.0441

Email: [email protected]

Comments (0)

Ask the author

0 comments