Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

How to Recognize and Clinically Manage Class 1 Malocclusions in the Horse

Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

Read

1. Introduction

A malocclusion is defined as any deviation from normal occlusion.1 In the horse, the normal occlusion (orthooclusion) is a level incisor bite. In humans (and many breeds of dog and cat), the incisors have a normal overbite. The hypsodont dentition, angled conformation of the temporomandibular joints, and anisognathism (mandibular jaw width narrower than the maxillary counterpart) result in the normal 10 –15° angle to the occlusal surface of the cheek teeth and enamel points on the lingual aspect of the mandibular cheek teeth and buccal aspect of the maxillary cheek teeth.2 The normal horse has a curvature of the occlusal surfaces of the cheek teeth in the longitudinal plane, called the curvature of Spee (Fig. 1). The rostral angulation of the distal cheek teeth and the caudal angulation of the mesial cheek teeth maintain tight interproximal contact until very late in life.3

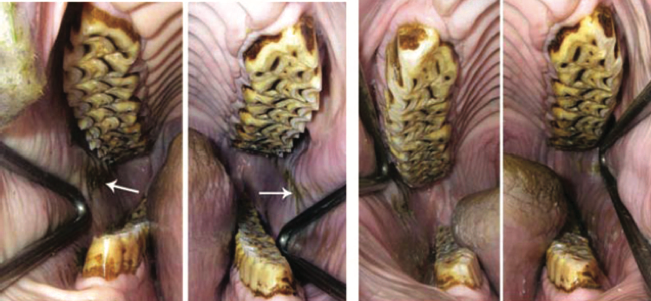

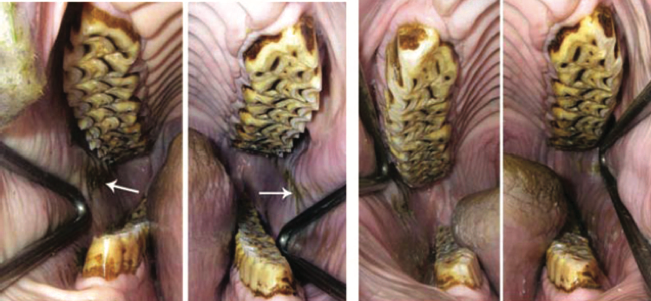

Fig. 1. Quarter Horse gelding, 7-yr-old. Normal development of sharp enamel points on the buccal side of the maxillary cheek teeth and the lingual aspect of the mandibular cheek teeth (left). Buccal mucosal lacerations (arrows). Normal curvature of Spee gives the false impression of a hook on the lower third molars (311, 411). Conservative management: floating of the anamel points; note that very little rasping of the occlusal surface has occurred.

A class 1 malocclusion (neutroclusion) occurs in horses with normal jaw lengths and teeth in their normal mesiodistal location. Abnormalities of cheek tooth wear are frequently seen and often described as waves, steps, hooks, and ramps.4 Although these types of occlusal abnormalities have not been previously classified as a type of malocclusion, their description as a class 1 malocclusion is justified and lends credence to the idea that occlusal adjustment is an orthodontic procedure. Similarly, abnormal incisor wear, given the descriptive terms smile, diagonal, stepped or irregular, and frown, can be considered another type of class 1 malocclusion.5

A malpositioned tooth, in the horse with normal jaw lengths, is another type of class 1 malocclusion. Rotations, embrications (crowding), displacements, and versions (tilting) are seen in both the incisor and cheek teeth, with the highest incidence in the Miniature Horse. An overjet is a facial projection of the maxillary incisors, whereas an overbite is the vertical overlap of the maxillary incisors over the mandibular incisors.6 The overbite (parrot mouth) is most commonly seen in the class 2 malocclusion, in which the mandible is short relative to the maxilla (Fig. 2). The maxillary incisor overbite or overjet may be accompanied by abnormalities in cheek tooth wear, such as hooks on the rostral maxillary and caudal mandibular cheek teeth. However, normal cheek tooth occlusion is often observed with these incisor malocclusions (Fig. 3). The class 3 malocclusion, in which the mandible is of greater length than the maxilla-incisive bones, is most commonly seen in the Miniature Horse. Mandibular incisor overjet or overbite may occur in the absence of cheek teeth abnormalities but is most commonly associated with ramped mandibular first cheek teeth (306, 406).

Fig. 2. Quarter Horse mare, 11-yr-old. Class 2 malocclusion (short mandible). Incisor overbite in conjunction with a normal cheek tooth occlusion.

Fig. 3. Warmblood X gelding, 14-yr-old. Incisor overjet, with ramp overgrowth of 206 and 311.

The etiology of class 1 malocclusions generally can be determined by physical examination and radiographic imaging. Because malocclusions can be responsible for poor mastication, periodontal disease, and poor athletic performance related to oral pain, proper diagnosis and management is important.

2. Materials and Methods

The equipment needed and method of performing a thorough physical examination of the horse’s head and mouth have been described.7 The clinician should perform a brief physical examination before sedation, noting the horse’s body score, rectal temperature, and in some cases, observation of the horse’s chewing behavior and whether quidding is present. An extraoral examination should include the observation of any facial swelling, nasal discharge, malodorous breath, ocular discharge, ptyalism, painful response to palpation of the temporo- mandibular joint region, and lymphadenopathy. After sedation, and before placement of the full-mouth speculum, oral examination of the lips, oral mucosa and gingiva of the lips and incisors, incisor malocclusions, and periodontal disease and assessment of the lateral excursion to molar contact is performed. After placement of the full-mouth speculum, the diastema between the incisors and the cheek teeth is examined, and the presence of canine teeth and first premolars (wolf teeth) is noted. The examination of the cheek teeth requires both an overall evaluation of the occlusion for patterns of abnormal tooth wear and a detailed, tooth by tooth examination with a good headlight, dental mirror, dental explorer, and periodontal probe. [...]

Get access to all handy features included in the IVIS website

- Get unlimited access to books, proceedings and journals.

- Get access to a global catalogue of meetings, on-site and online courses, webinars and educational videos.

- Bookmark your favorite articles in My Library for future reading.

- Save future meetings and courses in My Calendar and My e-Learning.

- Ask authors questions and read what others have to say.

Comments (0)

Ask the author

0 comments